FELIX SLATKIN AS SINATRA'S VIOLINIST AND

CONCERTMASTER:

Felix Slatkin served as Sinatra's violinist and concertmaster of

choice

on most of Sinatra's sessions at Capitol and Reprise up until

1963.

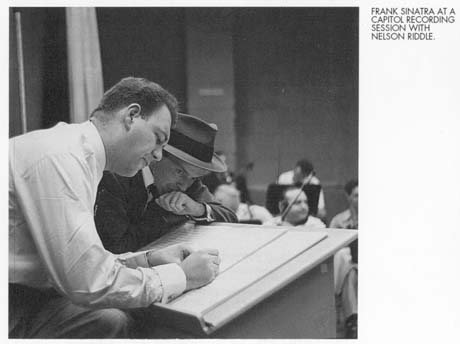

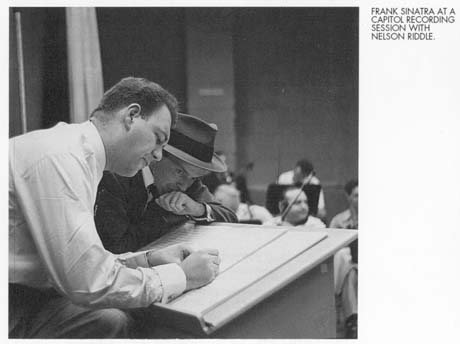

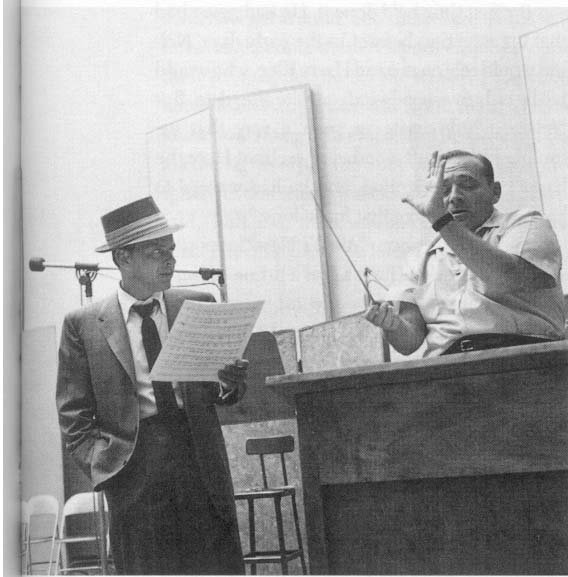

Slatkin is visible holding his violin bow in the above photo from a

Sinatra

session at Capitol in the 50's.

FELIX SLATKIN AS SINATRA'S CONDUCTOR:

Felix Slatkin conducted the orchestra on many Capitol and Reprise Sinatra sessions.

Sinatra speaking to Felix in the studio and calling him by name is preserved on compact disc. On the recording of "Only the Lonely" included as Track 3 of Disc 3 on the "Frank Sinatra: The Capitol Years" 3-CD set, the following comments by Sinatra to Felix are heard prior to the song:

"The whole orchestra should be fairly light...from the beginning of

the vocal, Felix - from about bar 11 on, let's keep the

orchestra

fairly light, until we get to the beginning of the crescendo...."

FELIX SLATKIN AS SINATRA'S ARRANGER AND CONDUCTOR:

Slatkin prepared the following arrangements for the following songs, and also conducted the sessions:

5/29/58:

"Monique" (Song From "Kings Go Forth") Capitol 4003

12/21/60:

"The Last Dance" Reprise (unissued)

"The Second Time Around" Reprise 20001

"Tina" Reprise 20001

NOTE: The following are excerpts from the book "Sessions with Sinatra" by Charles Granata, published by A Cappella Books (1999)

SINATRA AND THE SLATKINS

Eleanor Slatkin, who, along with her husband Felix, shared considerable social time with the singer, remembered "Frank was an unbelievable host. We were having dinner at his home one evening, and he had a gallery of paintings facing the dining room table-it was like a hallway. And I looked up, and said, 'Oh my God - that clown is absolutely incredible!' I went bananas over this painting, which he had done himself. When we left, it was in my car - he gave it to me! I have loved it for over forty years. Another night, Frank came to our house for dinner, and I couldn't get my sons to go to bed - you know, they were so excited. So Frank went upstairs, and sang to Leonard and Fred, and put them to sleep. And they have never, ever forgotten it - they simply adored Frank."

Leonard Slatkin, then a youngster, recalls: "As Frank began to work more and more with my parents, he began to develop a very striking friendship with them, and as a family, I remember several trips we took to Frank's home in Palm Springs, just to spend weekends with him, and for our families to be together. It was very exciting, but you know, as a young person, it just didn't seem to be that different. Sinatra had been over to our house several times, we'd been over to his house . . . it never occurred to me that he was a `larger-than-life' figure! He was just always `Frank,' and I think sometimes even `Uncle Frank.'

"Frank Sinatra loved young people. He couldn't have been nicer to my parents, and to us, and all the people we saw him with. And, yes - we had always heard that there were dark sides of Sinatra, but frankly, I never saw them. He was always gracious and generous. There were occasions after my dad died where I wrote Frank with the idea that perhaps we could collaborate on a project in St. Louis, and he always answered himself - it never came through his attorneys. He always answered them personally, and on a couple of occasions, he called just to chat," the conductor says.

Sinatra was among the first to call at the Slatkin home upon Felix's unexpected death in 1963, at age forty-seven.

"I wasn't dealing with it well," Eleanor recalled. "Frank set up a session at Goldwyn, The Concert Sinatra sessions. I wasn't really up to playing, but he said, `I won't play unless you agree to do the album.' He was trying to get me back, because I was nowhere. And finally, I said, `Okay,' and I broke down completely. He was responsible for getting me back in the business. He had principle, and he stood for what he believed in, whether you liked it or not. If he was a friend, he was a friend."

Says Leonard, "My father was an alcoholic, he smoked three packs of cigarettes a day, and he was overweight. So he had three strikes against him. When he died, I was the one who tried to keep calm in the family. My mom, I think, was confused by my father's death - she didn't know what to make of it. They'd had a rocky marriage; somehow, they'd always stayed together, but it had its problems. And Sinatra kept saying, `Anything I can do for you . . . but no matter what, you're my cellist.' And so he tried to bring her back, as a form of therapy (not that my mother needed it - she was a very, very strong woman), but perhaps to make her realize that friends and colleagues supported you in both ways, that they were not people who were going to abandon you, although some did. But Sinatra didn't. For some of them, all of a sudden my father wasn't there, and my mother was just a cellist . . . but Frank never felt that way. She was a friend first, who happened to be a cellist. I think he liked the idea that my mother would be a constant in his life as well."

CLOSE TO YOU (recorded 1956) - FRANK SINATRA with the HOLLYWOOD STRING QUARTET

Close to You, the first vocal album Sinatra recorded in the Vine Street studio, is a superb example of an album's evolution, and of how each element contributes to the overall success of the final recording.

In early 1956, inspired by the semi-classical overtones of Nelson Riddle's ballad orchestrations and the intimacy of the small group settings he'd crafted for In the Wee Small Hours, Sinatra engaged Riddle to orchestrate a series of tunes to be recorded with the Hollywood String Quartet (HSQ), a superior group comprising four of his most reliable session musicians: Felix Slatkin (violin), Paul C. Shure (violin), Alvin Dinkin (viola), and Eleanor Slatkin (cello). All were Hollywood film studio players, who fulfilled their passion for classical repertory by playing together in their offtime.

By 1954, the original violist, Paul Robyn, had left to pursue family interests, and his substitute was another Fox Studio colleague, Alvin Dinkin. Throughout the group's various incarnations, Felix Slatkin was the glue that held it together. "Felix was a wonderful violinist, and probably, to some degree, a frustrated man. I think he would have loved to have had a conducting career," remembered Shure. (Slatkin had in fact studied conducting, under Fritz Reiner of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Apart from the Quartet, Slatkin conducted numerous albums of orchestral music for the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and for Liberty Records.)

In Slatkin, Sinatra found a kindred spirit, as the violinist's immaculate playing paralleled what Sinatra sought to achieve with his voice; serious listeners will note many similarities when comparing Sinatra's and Slatkin's individual approaches to musical interpretation. One hallmark of the HSQ was its long, smooth phrasing, which was accomplished through controlled bowing techniques; Sinatra utilized breath control to realize the same effect. Likewise, where Felix would frequently add a slight upward portamento to a critical note and neatly strike an emotional chord, the singer would often inflect a note upward or downward or seamlessly glide from one key to another.

"My parents would talk to Frank very often about their own technique," said Leonard Slatkin. "He asked them questions. `What is that when you take the bow and you just kind of move it up and play several notes at a time? How do you do that?' he'd ask. He was fascinated by this, and my parents would say, `But Frank, we want to be able to imitate your voice!' I think that was a part of Sinatra's relationship with his musicians: there was a give-and-take, and everyone was interested in how each other produced what they did. Sinatra was always asking for advice to improve his singing, and they were always asking for advice on how to improve their phrasing vis-a-vis being more vocal in the way they played."

"The concertmaster was responsible for instituting a mutuality of expression," explains violinist Marshall Sosson, a close friend of both Slatkin and Sinatra. "The first chair violinist was the concertmaster, and he would set the bowing and keep the entire section working together. It was more important in the symphonic world; less so on these pop dates."

Slatkin was concertmaster for most of Sinatra's dates at Capitol and Reprise until his death in 1963, providing many of the piercing romantic violin solos that add color and dimension to Sinatra's finest ballads.

"Felix was always there for Frank," Eleanor remembered. "If he had a session elsewhere, he would cancel it and go to Frank's date. He really enjoyed Sinatra - but we all did. It was just sheer pleasure. Frank did, on many occasions, look to Felix for [musical] approval. Other people may not have been aware of it, but I was. And Felix loved it. He was flattered because he "idolized the man for what he was contributing." Sinatra was so excited by the way they played, the style, and sense of improvisation that they brought to the music, and he began to form a friendship with them," said Leonard Slatkin. "From that point on, my father served as not just the leader (concertmaster), but sometimes as contractor when there were disputes with other musicians."

Sinatra's appreciation for the classical genre enhanced not only his understanding of music, but his personal relationships with its musicians. While both Slatkins had begun performing at Sinatra sessions during the Columbia era, it wasn't until the Capitol period that their friendship blossomed. "We became very close friends and spent many weekends at his home in Palm Springs," recalled Eleanor Slatkin. "As you know, he has a tremendous collection of classical records, and every time we were at his house, he had classical music playing . . . and a lot of opera too. He is very knowledgeable, and of course, he knew many of the artists. He fell in love with the Quartet . . . we saw a lot of him in those days, between recordings and socially, and he said, `You know, I think it would be a terrific idea to do an album with a string quartet, . . . ' and so came Close to You. Everything you did with Frank was Frank's idea."

Although panned by critics upon its release, the album's magnificence was not lost on the musical cognoscenti. "My wife and I have been married for fifty-five vears, and she is a fine, classically trained pianist, vet we have both been fans of everything Frank ever did," says clarinetist Mitchell Lurie, who accompanied the Quartet on several tracks. "Not many people believe that as classical musicians, we're interested in listening to the 'other side.' That's just not true. We listen to this album often and we just wait for the next tune, and the next one, and so on - as if we were hearing it for the very first time." Lurie, like Slatkin, studied at Curtis in Philadelphia, and was a protege of conductor Fritz Reiner. He was a principal clarinetist with both the Chicago and Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestras, and occasionally with the Hollywood String Quartet.

From a thematic standpoint, of all the Sinatra LPs of his "golden" era, Close to You comes closest to perfection. The twelve tracks, as they appeared on the original LP (Capitol W789) poignantly convey the album's tale of lost love: "Close to You," "P. S. I Love You," "Love Locked Out," "Everything Happens to Me," "It's Easy to Remember," "Don't Like Goodbyes," "With Every Breath I Take," "Blame It on My Youth," "It Could Happen to You," "I've Had My Moments," "I Couldn't Sleep a Wink Last Night," and "The End of a Love Affair."

Like a three-act play, the album centered around three main songs and themes. Scene one: "With Every Breath I Take" - the confessional; scene two: "Blame It on My Youth" - the act of contrition; and scene three: "It Could Happen to You" - the admonishment.

Lasting a mere three minutes and forty-one seconds, Sinatra's reading of the Leo Robin - Ralph Rainger gem "With Every Breath I Take" is the epitome of finesse and should be required listening for anyone aspiring to sing a note of popular music. Riddle's elegiac touch provides first a trace of melodic support for the vocal, via Felix's violin and Julye's finely strummed harp. The nakedness of the barely whispered vocal against the simplicity of the orchestration brings each muted color into focus.

These songs sound so natural within this demure setting that it's nearly impossible to imagine them any other way - a more grandiose orchestral setting would destroy their bittersweet fragility. When sung by equally gifted vocalists, the songs just don't seem to communicate the same sincerity as Sinatra's Close to You.

The concept for this album was extremely progressive by the standards of its day. Where many operatic singers made successful transitions to the commercial pop side of the business, it was rare for a vocalist as firmly rooted in pop and jazz as Sinatra to venture over the classical. Even more unusual was the willingness of a pop arranger to cross it.

"It's the most stunning thing that Nelson Riddle ever did," believes Paul Shure. "Using the string sound as a basis rather than a pad or an enhancement really was a turnaround for Nelson. String quartet writing is the hardest thing to do, because everything is so open. With a larger orchestra, you have a big palette to work with, and there are all kinds of things going on. You can use the orchestra to overcome melodic deficiencies, by using riffs and doing things with the woodwinds or brass over a string pad and get away with it. When you're writing for four, six, or eight instruments, it's another story."

"I always like a big string section," Riddle once told British music historian and writer Stan Britt. "It's been hard for me to get used to chamber music and enjoy it. Not because of the orchestral colors, because they're rather sparse in chamber music; very often, chamber music is written for a string quartet. My original interest in writing arrangements came because of orchestral colors. I became fascinated with the harmonies and the various effects you could achieve with single instruments or groups of instruments of varying colors. Therefore, I'm always fascinated by large groups, and I find that small groups are more demanding in a way because you have less to work with. Now, Close to You utilized a string quartet . . . [but] when you're given an assignment, you don't sit there and quarrel about it."

As a young observer, Leonard Slatkin remembers that Riddle visited the Slatkin home many times during the planning of Close to You. "He was consulting with the Quartet day and night, just to make sure it was all done right. A lot of the things you hear in the album itself, and many other albums, is the result of input from other musicians," he said. Two classical composers whose influence can be clearly heard in his orchestrations for this album are the Impressionists Debussy and Ravel. Riddle's predilection for these composers began when he was a child. "I received a gift of an old-fashioned windup Victrola from my aunt Dorothy," he once recalled. "With it came a few recordings, among them a huge Victor Red Seal disc with 'Reflets dans L'eau' on one side and 'La Cathedrale Engloutie' on the other-two Debussy piano compositions peformed by Jan Paderewski. I probably blunted a bushel of cactus needles exploiting the wonders of those two treasures."

"He talked about Ravel and Debussy at home. He was so connected with the Impressionists," says Rosemary Riddle-Acerra. "I remember going to the symphony with Dad, and he was so based in the classics. He was quite friendly with Leonard Bernstein for a while, and Bernstein wanted to work with him on his conducting. He felt that he had a real sense of the music."

In describing the foundations of string writing to Britt, Riddle made the following points: "In order to get the full sound of the strings, string writing has to be developed from an almost 'classical' precept. To be able to balance X number of violins and violas, I believe that the rate is four violins = three violas = two celli. Because naturally, as the instrument descends (as it gets lower in pitch), the sound is thicker and more penetrating. You start with that. Then, you study string writing in general: what register the strings cut through best-where they are effective, where they are ineffective. All this evolves from listening to music, from studying scores, from being at sessions and listening to picture scores, and so on. Or from talking to violinists. That all sounds very calculated, and it was, and it's how I approached string writing. Also, through the classics - through Debussy and Ravel. Ravel, of course, was a marvelous orchestrator, from top to bottom."

"Nelson was influenced by those composers, and Villa-Lobos as well;' maintains Paul Shure. "He delved into the work of the Impressionist composers and tried to draw from the qualities and tonal palettes of that school of music, rather than from the Classical or Romantic school . . . it was quite a departure, and you can hear the early Impressionist composers in the feeling of the voice with the intimate (yet very beautiful) writing he did for the small combinations on this record."

A movement of nineteenth-century French painting dominated by artists such as Monet and Renoir, Impressionism also carried over to music, where its primary proponent was Claude Debussy. The French composer was among the first to express mood and atmosphere through pure tonal color, as opposed to traditional melody and harmony, in the process using new harmonies and scales that created room for new tonal possibilities. Essentially, the Impressionist style is evocative, "as vague and intangible as the changing lights of day, and the subtle noises of the rain and wind." Debussy was an influence upon Ravel, as well as Delius, Respighi, de Falla, Milhaud, and Dukas. Ravel is particularly important, as he is considered to be the father of modern orchestration, which is probably why so many arrangers look to his work for inspiration and guidance.

Close to You shows Impressionist influence, yet it is pure Riddle. "Nelson had his own sound, which was (even for the time) unusual because he might put one chord against another, the way that he does at the end of certain songs, or the sound of the three or four flutes that he has going on when the strings play. They're all typical Nelson Riddle gestures," explains Leonard Slatkin. Harp, via one of his signature glissandos or as a more prominent accent instrument, is also characteristic of a Nelson Riddle arrangement. While never lost in even the most raucous uptempo charts, harp creates an even more spectacular effect in this most intimate of settings.

Select accent instruments (clarinet, oboe, muted trumpet, flute) offset the formal sound of the Quartet without spoiling its integrity. "My guess is that adding the individual instruments to the Quartet was Felix's idea, because he always chose those of us that played with his group," says Mitchell Lurie. The supplemental instrumentation adds texture, and emphasizes certain moods. On "The End of a Love Affair," for example, the dark color of the oboe helps convey the loneliness Sinatra sings of; on "It's Easy to Remember," Lurie's clarinet provides an interesting contrast to the underlying string bed. A beguiling flute solo by Harry Klee is heard on the charming "Wait Til You See Her" - a recording that was excluded from the original vinyl album.

Segments of the original session outtakes reveal the sensitive care lavished on the album. The tide track, "Close to You," had been one of Sinatra's favorite songs from the time he published it with Ben Barton and introduced it in 1943 (it was his very first Columbia recording, done a cappella with the Bobby Tucker Singers). Riddle's knack for writing lines against both the vocal and the individual instruments is amply displayed here. For this, the album opener, Sinatra wished to create a subdued vet dramatic atmosphere, as the following dialog between him, Riddle, and harpist Kathryn Julye reveals:

Sinatra: The downbeats with the tremolo, the strings and the vibe:

is

that on the

same downbeat?

Riddle: The downbeat of seven, Kathryn. Are you playing octaves there?

Julye: I did - I played a couple of octaves.

Riddle: Just give me one note.

Sinatra: Just be real definite on those downbeats.

It is the loveliest arrangement of the entire recording. Accenting the solo violin opening are the tightly controlled harp and vibe parts, which then give way to the vocal entrance and the full quartet, firmly supported by a gently plunked, rich acoustic bass. The violins answer Sinatra's vocal lines in counterpoint, while in similar fashion the viola and cello pleadingly answer the violins. At the bridge, the string instruments play off each other in a call-and-response manner. After a gently syncopated harp accent, the violins "sing" the main part, while the viola and cello "answer" in the form of counter lines (in bold):

Violins: Close to you . . .

Viola and cello: Close to you, oh I'm so close to you . . .

Violins: I will always stav . . .

Viola and cello: Close to you, I'll stay so close to you . . .

Violins: Can't you see . . .

Then, as the pitch is taken up an octave:

Viola and cello: Close to you, oh I'm so close to you . . .

Violins: You're my happiness . . .

Viola and cello: Close to you, I'll stay so close to you . . .

The melody is constantly enhanced and reinforced not just by the vocalist, but by the individual instrumentalists as well-resulting in a fine cohesion of harmony and melody that strengthens the song's structure and increases its tension and drama.

Invaluable to the overall warmth of an orchestra's musical sound is the quality of the instruments. Nowhere is this more apparent than with string instruments, where lineage is as crucial as the player's training and technique. "A great instrument, being played on and cared for, will mellow and sound better as time goes on," explains Paul Shure. "The age of the instrument certainly affects what you hear, and that's the beauty of old Italian instruments. Keep in mind that the wood [maple and spruce] these instruments are made of was probably fifty or a hundred years old before the instrument was made. A good bow is even harder to find, and certainly affects the sound it draws. You can use two different bows on the same fiddle and get a completely different sound. The great bow makers' bows just draw a better sound . . . their knowledge of balance: and the way they cut the bow is a fine art."

For his Hollywood String Quartet performances, Felix Slatkin played a Guadagnini (1784) and a Guarnerius Del Gesu (circa 1730); Paul Shure chose an Andreas Guarnerius (circa 1691-stolen from the violinist in 1957) and a Vuillaume (1860); Eleanor Slatkin's cello was also a Andreas Guarnerius (1689); Alvin Dinkin's viola was an Albani (1711). Felix's Guarnerius Del Gesu was purchased from the estate of the late violinist Albert Spalding; it was the exact model that Jascha Heifetz played for most of his life. "It is the same caliber instrument as a Stradivarius, except it has a little more power," explains Marshall Sosson. These rare instruments are as costly as the finest works of art. In 1988, for example, a violin made in 1743 by Joseph Guarnerius Del Gesu sold for $915,200; the highest price paid at auction for a violin was $1.7 million in 1990 for a 1720 "Mendelssohn" model Stradivarius. A Stradivarius cello (circa 1698), known as "The Cholmondeley," garnered $1.2 million at auction in 1988.

Close to You belongs among the most artistic and most cherished recordings of the twentieth century. "My mother and father were about as proud of Close to You as they were of any of the albums they made of Beethoven or Brahms, because here was the preeminent popular musician of the time, having faith and confidence in doing something different. It wasn't a big seller in terms of Sinatra albums, but it was one of the most respected by everyone. I think my parents always felt that they had to do a good job and always be proud of it, because Sinatra went out on a limb for them," says Leonard Slatkin.

"It was a labor of love," concludes Paul Shure. "It was a joy to

record.

Frank was absolutely enthralled with the whole project, and what Nelson

came up with just blew his mind! We had no idea what we were getting

into

in the beginning . . . we just got together with these songs, and as

one

came to another and Frank started singing, we all got caught up in it,

and by the time we were finished, we were celebrating. We knew that

artistically,

we had something very good. We didn't know what was going to happen

with

it, but we sure knew there was something great there as far as the

artistic

endeavor was concerned. It was very satisfying."

ONLY THE LONELY (recorded 1957)

Nelson Riddle: "I was booked to do a tour of Canada with Nat Cole that summer and had hoped that maybe we could finish the album ("Only the Lonely") before I left," the arranger said. "I wrote all of the arrangements, but Felix Slatkin conducted the session.

Eleanor Slatkin distinctly recalled the singer expressing his pleasure with Slatkin's conducting and the outcome of the session. "We went out for a bite to eat afterwards, and Frank, right in front of Felix, said, `This is the marriage of a dream.' But then, Felix was a conductor. That's the difference - he turned every phrase to fit Frank. You have to be a conductor to do that - that the others couldn't do."

Most arrangers, by default, lead the orchestra for their recording sessions. Since conducting is a study unto itself, many orchestrators are not truly accomplished conductors, although their skill is sufficient to the needs of most pop recordings. Nelson had studied conducting with both Slatkin and violinist Victor Bay, but he wasn't a pro.

Warren "Champ" Webb, a fine woodwind player and personal friend, describes Riddle's conducting method. "Nelson was a superb conductor in this sense: he looked awkward-his hand-eye coordination was not the greatest in the world-but he listened to us. Whether we were doing a film or record date, we'd say, `Just give us one in every bar-that's all we need.' Then he'd become very relaxed, and he'd be able to conduct."

Pressured by the loss of the songs recorded at the May fifth session (this delayed finishing the album), Sinatra completed seven full songs at the Slatkin-conducted session of May 29, more than double the normal yield for a standard three-hour session. An eighth song planned for inclusion on the album, the haunting Billy Strayhorn classic "Lush Life," was attempted and ultimately left incomplete-possibly owing to the fatigue of such a long session.

While "Lush Life" is beautiful and well suited to interpretation by a vocalist with the dramatic flair of Frank Sinatra, it doesn't really fit into the overall scheme of Only the Lonely. Part of the reason is an awkward, out-of-meter piano introduction that evokes images of a honkytonk piano bar, blatantly out of character for the album's otherwise low-key atmosphere. The intro lacks the finesse and subdued sophistication so evident in the piano intro to "One for My Baby," the record's quintessential saloon song. Extant session tapes shed some light on what transpired in the studio and why Sinatra abandoned the song after three partial takes:

From the booth: "Master 19257, Take One." Bill Miller begins the piano intro, and after ten seconds, the take is halted. The tape is again slated: "Master 19257, Take Two." The piano introduction is completed, and a simple swell of strings spiral down, giving way to a harp glissando and Sinatra's entrance at the verse. "I used to visit all the very gay places/those come what may places/where one relaxes on the axis of the wheel of life . . . . "

Sinatra cuts the take. "Once more," he asks, vocalizing through the first few lines off-mike to get a sense of the timing. On the third take, which runs a little over two minutes, Sinatra gets through the verse and tentatively approaches the chorus. "Life is lonely/again, and only last year/everything seemed ..."

"Hold it!" he calls. "It's not only tough enough with the way it is . . . but he's got some slides in there!" Mockingly, Sinatra begins to joke, exaggerating his mannerisms. "Ooohh, yeah! Well, Ahhhhh . . . " From the booth comes the suggestion to put the song aside, and try "Sleep Warm." "Yeah, all righty now. . . ," Sinatra continues. "Put it aside for a minute," someone (possibly Slatkin) says, and Sinatra sarcastically retorts, "Put it aside for about a year!"

NICE ‘N EASY

Far more optimistic in spirit than Only the Lonely or No One Cares, the selection of tunes-all classic American popular standards-was matchless, and especially noteworthy since each of the twelve were rerecordings of songs the singer had sung at Columbia in the 1940s and early 1950s.

Realizing the importance of the songs and the value of Sinatra's updated interpretations, Riddle arranged many of the tunes to feature short instrumental solos. These simple vignettes brought freshness to the remakes and highlighted the capabilities of some of Sinatra's most cherished musical friends: Bill Miller (piano-"I've Got a Crush on You"), Plas Johnson (tenor sax - "Nevertheless" and "That Old Feeling"), Harry Klee (flute-"Fools Rush In"), George Roberts (bass trombone-"How Deep Is the Ocean?"), Carroll Lewis (trumpet-"She's Funny That Way") and Felix Slatkin (violin-"Try a Little Tenderness" and "Mam'selle").

REPRISE SESSIONS

While still under contract to Capitol, Sinatra had recorded five full albums for Reprise: Ring-A-Ding-Ding!, I Remember Tommy, Swing Along with Me (later retitled Sinatra Swings! after yet another legal battle with Capitol, this time over Reprise's use of similar thematic album titles), Sinatra and Strings, and All Alone. Sprinkled among the LP recordings was a handful of pop-oriented singles, including three songs conducted by Felix Slatkin.

Sinatra had offered Slatkin the musical directorship of Reprise Records as soon as he formed the company. "My father was to be the chief A&R man, as well as Sinatra's producer and arranger," remembers Leonard Slatkin. "He stayed with Sinatra for a little while and then got an offer to go over to Liberty Records with a man named Simon Waronker. Liberty Records provided my father with a little more flexibility, and the chance to do more producing and conducting, plus, he retained part ownership in the company. Even during that time, though my father's focus had shifted to a different entity, Sinatra remained faithful." The bright young arranger Neal Hefti filled in for Slatkin when he left Sinatra's employ.

RING A DING DING (recorded 1961)

Unedited tapes reveal a remarkably jovial tone for these sessions. In the studio, there is electricity in the air; the atmosphere is light and fun. The, musicians are warming up, joking, and laughing, as though the event weren't so much a recording session, but a real fun evening out with "the guys." One of the women - Eleanor Slatkin, or Sinatra's secretary, perhaps - is heard greeting a guest with a warm, sincere twinkle in her voice. "Thank you dear, thank you ever so much for coming . . . I certainly do appreciate it!" The conviviality is palpable-even infectious. Happy sounds come from the piano, the horns, the percussion, as they find their pitches.

Shuffling lead sheets at his music stand, Sinatra, anticipating one hell of a swingin' evening, addresses Mandel. "I'll tell you what we do, Johnny . . . let's do the title song, huh? Yeah, let's get into the mood with it!"

"Ring-a-Ding-Ding," Mandel calls out. "That's the name of the album, so let's get in the mood," Sinatra says, walking among the band, priming the musicians. He checks in with Felix Slatkin, who is producing from the booth. "Feel . . . ?"

Slatkin's voice comes back over the talkback system. "Ring-a-Ding?"

"Get everybody in the mood... ," Frank says. "Let's do about sixteen bars for balance, so we can get an idea of what we're doing. Then we'll do a test . . . run a test to see what we got."

As the musicians finish tuning up, Sinatra prepares for the recording test on the title track. To the soundtrack of Irv Cottler adjusting his snare drum and hi-hat cvmbals, Sinatra begins singing and snapping his fingers sharply, trying to feel the groove that works best for the record.

Life is dull . . . it's nothin' but one big lull . . . and presto you do a skull . . . ba-daba-da-ba-bop . . . ba-da-ba-da-ba-beep . . . do-do-do-dee-do-doo . . . .do-de-do-do-dode-do-do . . . do-de-do-do. . . do-de-do . . . [speaking] should be right . . . SNAP! . . . about . . . .SNAP! . . . in . . . SNAP! . . . there . . . SNAP! . . .

The tempo now set, Sinatra continues to snap his fingers decisively, and Mandel, after taking a moment to match the pacing Sinatra has delineated, counts off to cue the band. "One, two, three, four!" The rollicking sound of one great big band blares forth. After the test take, it is clear that Sinatra has a winner on his hands, and the rhythm section breaks into a celebratory jazz-club style improvisation of the song.

"HAVE YOU MET MISS JONES?"

"Have You Met Miss Jones?" is a pretty song: soft and light in the hands of Johnny Mandel. Even as the orchestral run-through of the song begins, though, problems crop up. Musicians, confused about what keys their parts have been written in, start to compare notes. "We've got B-flat." "We have A-flat." "Should there be a G in bar fifteen, or an F?" "It should be a G instead of an F."

All this ado prompts Sinatra to start making wisecracks. "You guys are in a lot of trouble tonight . . . A lot of trouble tonight. I think the copyist is drunk! Does Vern Yocum drink? Jesus!" he says.

One of the musicians, offering an opinion, confirms that Yocum is a teetotaler. Another guy in the band, clearlv joking, quips back, "Well then he's a junkie!" "Maybe you got the wrong arrangement. You got the right arrangement up?" Sinatra jokes.

More notes are corrected, and moments later, Mandel counts off for another try at the tune.

The introduction is celestial: the winsome tones of Bud Shank's flute (Mandel's signature woodwind sound) are nestled among the soft sheen of a light bed of strings, to which both harp and bass have been discreetly added. .After mere seconds, Sinatra comments on the difference of the arrangement's feel, as compared to the balance of the charts. "This sounds like a different album."

After another minute or so, the instrumental rehearsal breaks off, and more corrections are discussed. Sinatra's voice is not angry, but deliberate: you can sense that he is becoming impatient. "Jesus Christ, this is brutal," he says. He calls to an aide. "Eddie Shaw: call up Vern Yocum, and tell him that from hereon in... from this minute, whatever he's copying, for Christ's sake to get the notes right! Jesus, this is murder!"

Slatkin, sensing Sinatra's concern, reassures him. "We'll run this down, Frank. Wanna put it on tape and listen to it?" The singer, perusing his lead sheet, is being thrown by the number of mistakes in the chart. "Are there A-flats in fifty-six? That's what it sounds like to me. Felix? Shouldn't there be A-flats in bar fifty-six? It sounds a little crazy." Mandel takes the orchestra from bar fifty-three and resolves the problem.

After some more tinkering, Slatkin asks if they should drop the tune. "Uh, whaddya think about this? What about this tune on the album?" Sinatra: "We'll try it and see what happens." Slatkin: "It's a lot different . . . unless we can pick up the tempo," he suggests. Sinatra: "We'll run it down first and see what happens. . . "

In the end, it didn't happen. After a full yocal run-through in

which

the tempo was increased to medium, it was obvious that the beauty of

the

chart as originally written was marred; after finding some additional

problems

with incorrectly transcribed notes, Sinatra simply calls for the next

tune.

"I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm," he requests. "Pass this." (He must

have admired the tune, because five months later, in May 1961, he made

a striking recording of it with Billy May for Swing Along with Me).

"A FOGGY DAY"

A tune that is definitely Mandel's is a cookin' version of Gershwin's "A Foggy Day." Sinatra likes the bells, which set the stage for his Londonderry excursion. During the rehearsal, he jauntily hums along, at one point during the bridge calling across the studio to Mandel, "Good tempo, John."

When the run-through is complete, he offers some musical suggestions, both about the bells and some brass accents, to both Mandel and Slatkin. "Those brass notes you've got from fiftyone on . . . try not to rush those, it sounds like it's rushed. Don't jump at'em . . . don't jump at'em. Pop, pop, pop, pop . . . very relaxed." As the band plays through the particular section where the notes crop up, Sinatra points them out to Mandel. "Whoa . . . those notes . . . okay!"

Then, addressing Slatkin, he, discusses the instrumental bridge: "Felix, beginning in bar fifty-five, I want to get a feeling of a concerted crescendo all the way up through sixty-five, sixty-six, sixty-seven, sixty-eight, sixty-nine, boom! the cut-off." Slatkin agrees. "Yeah, that's great, Frank, but I tell ya, if they would do it out there, it would help a great deal," Slatkin says confidently. "That's what I'm talking about . . . but I want you to listen to it . . . ," Sinatra tells him. Slatkin clarifies who will be responsible for accomplishing the desired effect. "We won't build it in here too much: we'll hold it, and let you build it out there." Sinatra agrees. "No, no, no, no not you," he says.

Mandel leads the band in a run-through, and at the end, Sinatra asks, "All right?" "Yeah, good!" Slatkin announces. "Really whack those chimes when we get in there," Sinatra tells percussionist Emil Richards, who nods. "Right."

"All right, let's try it, huh?" the singer says. Slatkin gets things underway. "Ready to go, John? We are rolling . . . this is M-103, Take Two."

Appropriately punchy, chimes thoroughly whacked in exactly the right spots, the performance emerges as one of the best of the lot. The conversations heard on these particular sessions underscore how Sinatra has honed his command of rhythm and musical nuance to perfection.

Having sharpened his rhythmic sense with Riddle and May at Capitol, he could now take bold control, easily communicating what he believed to be the appropriate, "in-the-pocket" groove to those responsible for executing it.

"LET’S FACE THE MUSIC"

For example, as the group is about to begin a run-through of "Let's Face the Music and Dance," we find him characteristically humming, singing, and snapping, suggesting a tempo to the musicians. "In the first chorus, gentlemen, think of this thing in a fat `two: Just think of it that way. The rhythm's gonna play in a big, broad `two: Let's try it." The recording is made, a playback listened to.

Take one of the song, master M-104, is taken at a brighter tempo than subsequent takes. In the studio, Sinatra realized that maybe it was a bit too fast, and made the call to adjust the tempo. "I think it's gonna come down a little more," he says, humming the tune. His finger snaps begin to slow. "We've got another change. Irv, it's coming down a little more. Yeah, yeah . . . try it at this tempo," he instructs. His assessment of the proper tempo is uncanny; his judgment, right on the money.

SINATRA AND STRINGS (recorded 1962)

Sinatra's son also recalled the very first session for the album. "They assembled the huge orchestra... and the old man walked in that night for the first take, `Hey, hey: ring-a-ding-ding!' And he was playing with his hat and everything, and he saw the concertmaster, Felix Slatkin, slumped over in his chair. Felix had his violin still in its case, across his lap. He was sweating. He looked up and said, `Frank, I don't feel good.' My old man turned around and looked at Costa with all the music, and the fifty musicians. But the concertmaster didn't feel well. So Dad turned to Hank Sanicola and he said, `Hank, pay everybody off.' And he got up on the conductor's podium, [tapped on the stand] and said, `Everybody, good evening. Turn in your W-4 forms, we're not recording tonight. Come back tomorrow night at eight.' Pushed the whole album session back one day! Slatkin was not well, and he was not going to record without his concertmaster. Paid everybody off and sent them home. Got to do it right."

Leonard Slatkin's reminiscences:

"Uncle Frank: Sinatra and the Slatkins"