INTERVIEW WITH ROY

LEE BROWN - PART 2

(interview recorded by Bill Thompson on 4-18-04)

SATURDAY NIGHTS AT CRYSTAL SPRINGS

On Saturday nights at Crystal Springs, they started at 9 and played

until 2 in the morning, and they didn’t take an intermission. Usually,

if they took an intermission, fights would start. If you took the

people who had danced and the ones that had drank, and the ones who danced

AND drank, by 12 o’clock they were having a big time and they might be

getting a chip on their shoulder and were ready to fight sometimes.

So Milton didn’t allow them to take an intermission on Saturday night.

If a Brownie needed to get down and go to the restroom or whatever, the

rest of the band carried on playing without them.

I started going to Crystal Springs when I was 12 years old.

My dad didn’t want me to go down there. If it hadn’t been for Milton

and Derwood saying “Oh Dad, let him go down there, we’ll watch after him”

then Dad wouldn’t have let me go. But even then, I had to be home

at 12 o’clock. I had to catch a bus or somebody had to bring me home.

I never did get to stay until 2 o’clock.

Sometimes they would have a guest vocalist. Jimmie Davis

would come by there sometimes and sing with them. He used to go fishing

somewhere up in North Texas, and he thought there was nothing like the

Brownies. Best of my recollection, he would just sit up there in

a chair on the bandstand close to Wanna Coffman, who played the bass.

He would sip on his little whiskey or honey or whatever he had in that

bottle. I was told by Wanna that he did sing with the band from time

to time. Jimmie Davis put out some hit songs that he had bought

off of prisoners down there at Shreveport. He was some kind of peace

officer down there. That’s where he got most of his songs.

“You Are My Sunshine” and a bunch of them. He’d bail somebody out

if they’d give him the words to a song. Jimmie Davis had trouble

with meter. He couldn’t keep meter. When he was recording,

he had a man there to tell him when to come in to sing. Back in those

days, I heard him break meter on several tunes.

They had one microphone, and that was for the vocalist; the same

microphone was used for the fiddles - the vocalist would step aside for

them. Bob Dunn had his own amp, a "Volu-Tone".

This was the first amplified steel used in a western band. They had

no drums. Fred Calhoun played good rhythm on piano. Most of

the dance halls had a piano, but they were in terrible shape.

They ran into that a lot when they were on the road.

I have a friend whose mother-in-law said she used to go see the Brownies

close to Waco at another little town down there. She was going to

school down there as a young girl, and went to one of their dances.

She said the piano was broken down, and it took Fred Calhoun until intermission

to get it fixed so he could play it. I ran into that problem myself

when I was playing dates around Fort Worth. The piano was in there,

but there was no telling how long it had been since it had been tuned,

and maybe kids had played on it and banged on it, and no telling what was

broken about it.

The fiddle players would be close to the mike at all times.

On the other side of the mike was Derwood, with Milton in the middle.

That

way they could move back or forth and could step up closer to the mike

as needed. If any of them was going to “take a ride”, then they would

step up close to the mike, and then step back when they were finished.

RECORDING SESSIONS

They just did one take on their recordings. That’s why you’ll

hear some mistakes in there. Derwood left out part of the song on

“Brownies Stomp”. Any other band would have been thrown so far off

they would never have recovered. But the Brownies came right in behind

him like it was planned that way. In fact, I’m not sure it wasn’t

planned that way - it sounded so good! But I listen to it and I say

“Wait a minute - there’s something wrong there!”

On “Garbage Man Blues”, Milton started the song singing in a different

key from the band. I don’t know how he got that high, and he didn’t

do it very well. But by the end of the song, he corrected for it.

It’s a real unusual recording.

Milton didn’t play any instruments - just never showed any interest

in it. But he sang all the time. If he was awake, he was singing!

When we lived out on Roberts Cutoff, I’d ride into town sometimes on Saturday

with him, because I was out of school. They had a radio program on

Saturday. Sometimes they would say, “Do you want to do a song on

the program?” It didn’t matter to me. I wasn’t trying to be

a singer, but I would go and do some Jimmie Rodgers song or some prisoner

song along with the original Brownies. When they were at the station

in the Texas Hotel in Fort Worth, I was 12 or 13 years old, and Milton

would say, “Roy Lee, you want to do one on the program today?” And

I’d say “I don’t care.” I’d be going into town anyway to a shoot-em-up

western movie down on lower Main Street and watch a double feature before

I would come home. So I would go on up to the program first.

I’ll tell you another thing about Milton. The studio was on

the mezzanine floor of the Texas Hotel at 8th and Main Street. Usually

we couldn’t park right next to the hotel, so we would park and walk a block

or two. We’d walk down the street, and I guarantee you, in one block,

he’d shake hands with four or five people who knew him. That’s how

well he was known in Fort Worth. Then we would go on up to the station.

When I left there, I was headed for the movies.

WBAP was on the 22nd floor of the Blackstone Hotel. That’s

where they broadcast Milton and the Brownies’ program. Then when

Derwood took over, he broadcast from there until they put his time too

far. Instead of firing the band, they set his time up too late, about

2 PM. That kept them from getting to their dance booking on time.

So Derwood said “We can’t do that.” So they went back to KTAT.

But that station only goes out about 130 miles.

You may not know that Milton had a saxophone in his band for about

8 months. His name was Iris Harper. He and I used to have a

feet fight on the bus. He rode right ahead of me, and he was always

trying to take up my space. We were always kicking each other!

But he didn’t stay with it, and Milton didn’t get another horn player.

Of course Bob (Wills), he switched to horns. Those horn players

were coming down there to Crystal Springs all the time anyway. If

Milton had a big job, like the Automobile Building in Dallas, he would

hire drums, a trumpet man, and a sax, or maybe two of them. Then

he would have to rent 2 big speakers and hire some off-duty policemen to

take care of the crowd. They still made big money out of it, even

after all that expense.

They made more money than any other band around. They were

all driving new cars - I don’t think any of them were paid for, but they

could afford the payments.

A. B. GILBERT

A. B. Gilbert was a long-time fan of Milton Brown and the Brownies.

He used to listen to the Light Crust Doughboys when they first came on,

and then later he listened when Milton left and started the Brownies.

But while they were with the Doughboys, A. B. Gilbert told me that he and

a friend rode into Fort Worth on horseback from Santo, Texas, which is

on the other side of Weatherford. That’s a pretty good horse

ride from there. They spent the night sleeping out on the prairie

- it was summertime and warm weather. It seems like he said they

went to the studio where the Light Crust Doughboys were playing.

The next day they rode back to Weatherford, and the Light Crust Doughboys

were over there doing a program. The governor of Oklahoma,

Bill (?) had come down - I’m not sure why he was there. There was

an old song that Milton and Doughboys sang that day called “On My Farm

in Louisiana Where the Old Red River Flows”. Milton changed

the words for the governor, and sang “On My Farm in Oklahoma Where the

Old Red River Flows.” That’s the way Milton would do. He would

adapt songs and improvise lyrics to fit the occasion, which most people

would never think of doing.

When Cary Ginell came down to Texas and we started to research our

book, Smoky Montgomery had a recording studio over in Dallas, and so we

made arrangements to go over there several years in a row. We got

together as many of the old musicians that played back in the ‘30’s as

we could, like Zeke Campbell, Smoky, Fred Calhoun, and all of them that

we could, and we would have a jam session. Then they would

always take a picture of the whole group. I have that picture in

a frame, and I loaned it to the Cowtown Museum of Western Swing.

I also have my picture down there because I was inducted into the Cowtown

Society of Western Music. I have Milton’s picture there, and

Derwood’s boys have his picture in there also. I don’t have

a whole lot of memorabilia, except pictures. And I have an old 78

record or two. One of the records is “Precious Little Sonny Boy”,

which Milton wrote about Derwood’s boy. It’s not a whole lot, but

I wouldn’t want to lose it, because I’ve lost so many pictures through

the years. People have good intentions of returning things, but many

times they never bring them back.

MILTON'S CHARLIE CHAPLIN FIGURINE

I

want to show you something and tell you a little story. Here

is a little glass figurine of Charlie Chaplin standing next to a barrel.

You see the barrel has been broken around the top. But back when

Milton was 12 years old, they lived there in Stephenville.

He took appendicitis. Stephenville didn’t have a hospital, and there

was no way those doctors would even do an appendectomy at the time, so

my dad had to put Milton on the train, and they had to go to Dallas to

go to the hospital there for the operation. On the way over there,

Milton’s appendix burst. When they got over there, they operated

on him, and then they had to go back in there twice. They had to

put a tube in there so it would drain. It really was serious.

Well, while he was in the hospital, my dad was the only one with him, and

he went out to some store and bought this. Charlie Chaplin

was very popular back then (about 1915). The barrel beside the figurine

was filled with tiny candies which were harder and smaller than today's

"Tic-Tac" mints). He gave it to Milton, and Milton hung on

to it. Through the years, it has gotten broken around the top here.

My mother and dad had it, and when they passed away I got it. It

used to have a lot of paint on it, but now you can barely tell it was painted.

I’ll bet it didn’t cost over a dime or fifteen cents back then.

I

want to show you something and tell you a little story. Here

is a little glass figurine of Charlie Chaplin standing next to a barrel.

You see the barrel has been broken around the top. But back when

Milton was 12 years old, they lived there in Stephenville.

He took appendicitis. Stephenville didn’t have a hospital, and there

was no way those doctors would even do an appendectomy at the time, so

my dad had to put Milton on the train, and they had to go to Dallas to

go to the hospital there for the operation. On the way over there,

Milton’s appendix burst. When they got over there, they operated

on him, and then they had to go back in there twice. They had to

put a tube in there so it would drain. It really was serious.

Well, while he was in the hospital, my dad was the only one with him, and

he went out to some store and bought this. Charlie Chaplin

was very popular back then (about 1915). The barrel beside the figurine

was filled with tiny candies which were harder and smaller than today's

"Tic-Tac" mints). He gave it to Milton, and Milton hung on

to it. Through the years, it has gotten broken around the top here.

My mother and dad had it, and when they passed away I got it. It

used to have a lot of paint on it, but now you can barely tell it was painted.

I’ll bet it didn’t cost over a dime or fifteen cents back then.

DEACON ANDERSON

(The

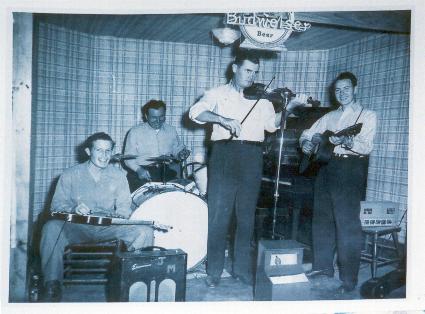

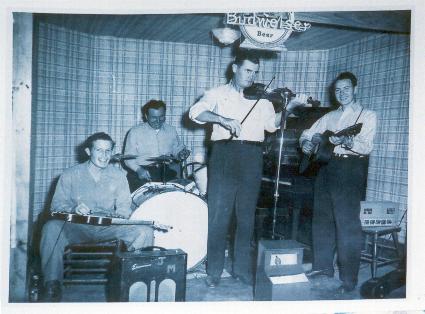

picture of Roy Lee’s band in the ‘40’s:)

(The

picture of Roy Lee’s band in the ‘40’s:)

Deacon Anderson, steel guitar. Curley Hallmark, drummer. Ollie

Burns, fiddle. Roy Lee Brown, guitar.

Deacon played more like Bob Dunn than anybody else. Of course,

everybody who played lap steel guitar at that time tried to copy Bob Dunn

because he was the daddy of it. He was the first one who used that

type of steel guitar - it wasn’t Hawaiian guitar, it was steel guitar.

A lot of people took their regular acoustical guitar and you could buy

a bridge for it at the music store to raise those strings up, putting them

under the nut and under the bridge. Then they sold those steel

and the picks, and lot of people did their own homemade steel guitar that

way. That’s what Bob Dunn did at first. And then he would

take a V-shaped magnet and magnetize those strings every night before a

dance and every day before the radio program to give it more resonance,

more ring to it. Bob Dunn had a DeArmond pickup that sat under the

strings, and it had no magnet on it, or at least it didn’t magnetize the

strings like they do now.

Our band played at the Dude Ranch in Fort Worth out on Azle Avenue.

That was right after I got out of the service, 1946 or 1948. We had

an amp for the PA system. In the picture you can also see the

“kitty” for people to drop money into. The guitar I’m playing

in the picture is the same one I have today.

When I did the CD for Rodney Moag, old Deacon was there and played

steel (guitar) on it. So when I went in and met him, he said “Well,

we haven’t changed much!” and I said “Oh yes we have! I’m gonna show

you.” And I went and got this picture and brought it in and showed

it to him. We’ve changed a whole lot!

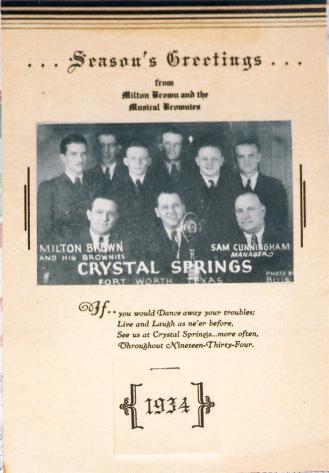

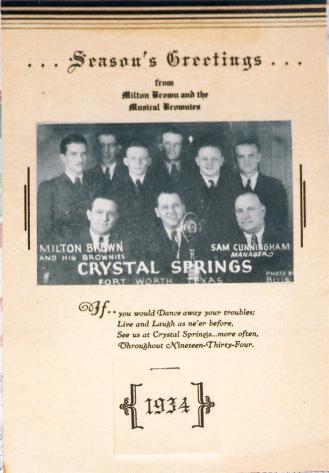

THE 1934 BROWNIES CALENDAR

Whoever would write in to the Brownies at Crystal Springs, they would

send out this calendar. It came out in late ’33 and it’s a

calendar for 1934. This one was never sent out because the envelope

is unmarked. These are selling for about a hundred dollars now, if

you can even find one. One guy asked me to get him one, and

I told him “I can get it for you, but it will be a hundred dollars,” so

he sent me a money order and I got it and sent it to him. It was

nearly as good a shape as this one. The guy that got these calendars

- I don’t know how many he’s got, maybe four or five - I think he picked

them up at a flea market or something. He gets a mint for them, because

there’s no more of them.

The poem on the calendar reads:

If you would dance away your troubles,

Live and laugh as ne’er before,

See us at Crystal Springs more often

Throughout 1934.

Season’s Greetings from Milton Brown and the Musical Brownies

TEXAS WESTERN SWING HALL OF FAME (San Marcos)

In 1999 I was inducted into the Texas Western Swing Hall of Fame

in San Marcos. Of course, I had already been down there to

accept the awards for the Brownies and to present awards to other people,

even Jesse Ashlock. I presented his award to his wife; of course,

Jesse had already passed away, but they awarded it to him posthumously.

In 2003, the Texas Western Swing Hall of Fame inducted Derwood Brown.

Derwood's sons Ronnie and Milton "Sonny" Brown accepted Derwood's award.

COWTOWN SOCIETY OF WESTERN MUSIC (Fort Worth)

In May 2000, they had the first Cowtown Society of Western Music

awards, and I was one of the first ones inducted into that. They

called us “Heroes”, and I’ve got a medal in there.

In 2001 they began inducting people posthumously. That’s when

Milton, Derwood, Cecil Brower, Bob Dunn, Fred "Papa" Calhoun and others

were inducted. I accepted Milton’s medal.

In 2003, they inducted Wanna Coffman. We couldn’t locate any

of his relatives, so I accepted the medal on his behalf.

Also in 2003 they recognized Crystal Springs as the “Venue of the

Year”. So I accepted that award and told about Crystal

Springs, because so much of the history of my family happened at Crystal

Springs. That’s where Western Swing started. My two brothers

were the ones that had the band that started it there. Crystal

Springs is where I learned to swim; where I learned to dance; and where

I met my wife of 66 years, Ellen.

This year (2004), they’re having it on May 1st at River Ranch on

the north side of town. I’m going to attend, but I don’t know

about any awards that I will have to present or to accept for people.

(The medals are inscribed “Western Swing Hero”, and has crossed fiddle

and bow with a Lone Star and Texas flag in the background. In the

photo, from left to right, you see Wanna’s, then Roy Lee’s, then Milton’s.

)

ROY LEE'S RECORDS AND BANDS

I had the Junior Brownies in the ‘30’s, while Derwood was leading

the Musical Brownies. We were a bunch of teenagers, so we called

ourselved the Junior Brownies. We had shirts that said Junior Brownies

on the back. We played wherever we could, and tried to make a little

money out of it; we didn’t make much, but anyway it kept us busy and out

of trouble sometimes.

Through the years, people have come to me and said “Why don’t you

record some of the songs that Milton used to sing?” And so

finally I was able to do that, and I recorded my tapes. I couldn’t

have done it without the help of Johnny Case and some other great musicians.

It costs money to do CD’s or tapes, and I just never had the money to do

it. You don’t get that much out of it, unless it’s a tremendous

big seller. I might have gotten most of my money back, but that’s

about it.

I released two records earlier in 1949. They were 78’s on the

Swing Records label, which were pressed up in Paris, Texas. We recorded

them in Fort Worth at McLister’s Recording Studio. That’s when I

had a band playing at Hillbilly Inn. Those records never did do a

whole lot. Those have never been re-released, but I did re-record

“Don’t Ever Tire of Me” on my recent tapes. One of the

other songs was sung by Earl Milliorn, who played rhythm guitar in the

band. It was a sad song, and I never did want to put that on my tapes.

Another one was a party song that I didn’t want to sing again.

I know two disc jockeys in Poukeepsie, New York and they call me

occasionally and try to get as much information as they can. This

one guy found my record of “The Iceman Song” at an auction. He interviewed

me over the phone to see when it was made, and who all I had in the band.

He said he was going to play that interview on his radio program.

I think he owns the radio station - it’s probably a very small place.

Then there’s DJ from a country station - I think his name is Darwin Lee

Hill. He puts some of mine and Milton’s music on his show.

You’d be surprised at how many people up north like this kind of

music. This guy that just passed away recently, Jim Grimm, he was

originally from Philadelphia. I had talked to him on the phone

a number of times, but we had never met. I finally met him down at

San Marcos one year. He told me a story that when he was playing

country and western music up there in New York City, this woman came up

to him.

She said “Can you play Truck Driver’s Blues?”

He said, “No, I don’t believe I ever heard that.”

She said “You never heard of Truck Driver’s Blues?”

He said, “No, I don’t believe I have.”

She said “Milton Brown recorded that.”

He said “I’m not familiar with Milton Brown.”

She said “You don’t know Milton Brown?!”

He said “No…”

She said “You don’t know NOTHING!”

Of course, Milton never recorded that; Cliff Bruner recorded it.

She had her wires crossed - but at least she made her point!

That was the first truck-driving song ever recorded.

Anyway, I had gone to work on the Fire Department, and my playing

was getting more popular around Fort Worth, and I couldn’t keep playing

and still do my job justice. I had a more secure job with the Fire

Department, so I quit having a band and I joined a little band that just

played on the weekends at different places, mainly night clubs and beer

joints on the highway. The people would come in there and dance.

We had a small combo, usually three or four people. The money

they paid the band, they had to make it off the bar, because there was

no admission charge. So they had to sell a lot of high-priced beer

in order to pay the band. A lot of places couldn’t afford a band.

Go on to Part 3 of

the Interview

Back to the Roy Lee Brown Page

I

want to show you something and tell you a little story. Here

is a little glass figurine of Charlie Chaplin standing next to a barrel.

You see the barrel has been broken around the top. But back when

Milton was 12 years old, they lived there in Stephenville.

He took appendicitis. Stephenville didn’t have a hospital, and there

was no way those doctors would even do an appendectomy at the time, so

my dad had to put Milton on the train, and they had to go to Dallas to

go to the hospital there for the operation. On the way over there,

Milton’s appendix burst. When they got over there, they operated

on him, and then they had to go back in there twice. They had to

put a tube in there so it would drain. It really was serious.

Well, while he was in the hospital, my dad was the only one with him, and

he went out to some store and bought this. Charlie Chaplin

was very popular back then (about 1915). The barrel beside the figurine

was filled with tiny candies which were harder and smaller than today's

"Tic-Tac" mints). He gave it to Milton, and Milton hung on

to it. Through the years, it has gotten broken around the top here.

My mother and dad had it, and when they passed away I got it. It

used to have a lot of paint on it, but now you can barely tell it was painted.

I’ll bet it didn’t cost over a dime or fifteen cents back then.

I

want to show you something and tell you a little story. Here

is a little glass figurine of Charlie Chaplin standing next to a barrel.

You see the barrel has been broken around the top. But back when

Milton was 12 years old, they lived there in Stephenville.

He took appendicitis. Stephenville didn’t have a hospital, and there

was no way those doctors would even do an appendectomy at the time, so

my dad had to put Milton on the train, and they had to go to Dallas to

go to the hospital there for the operation. On the way over there,

Milton’s appendix burst. When they got over there, they operated

on him, and then they had to go back in there twice. They had to

put a tube in there so it would drain. It really was serious.

Well, while he was in the hospital, my dad was the only one with him, and

he went out to some store and bought this. Charlie Chaplin

was very popular back then (about 1915). The barrel beside the figurine

was filled with tiny candies which were harder and smaller than today's

"Tic-Tac" mints). He gave it to Milton, and Milton hung on

to it. Through the years, it has gotten broken around the top here.

My mother and dad had it, and when they passed away I got it. It

used to have a lot of paint on it, but now you can barely tell it was painted.

I’ll bet it didn’t cost over a dime or fifteen cents back then.

(The

picture of Roy Lee’s band in the ‘40’s:)

(The

picture of Roy Lee’s band in the ‘40’s:)